Mr. Scorsese Review: A Deep Dive into the Legendary Filmmaker’s Life and Cinema

A new behind-the-scenes documentary about Martin Scorsese covers everything from his near death from drugs to the religious vision that shapes his work. It’s essential viewing.

By the late 1970s, legendary filmmaker Martin Scorsese had partied through Hollywood so intensely that his body was ravaged by drugs, leading him to a hospital with internal bleeding. “I was dying,” he candidly admits in Rebecca Miller’s enthralling documentary series, Mr. Scorsese. His steadfast friend, Robert De Niro, visited his bedside, urging him once more to pursue a film project Scorsese had been resistant to. Scorsese vividly recalls De Niro’s words: “He looked at me and said, ‘What the hell do you want to do? Do you want to die like this?’” This pivotal moment set in motion the creation of the now-classic film, Raging Bull. The story concludes on a brighter note, with never-before-seen photos of Scorsese and De Niro, looking relaxed in Hawaiian shirts and goofy tourist hats from St. Maarten, the Caribbean island where they collaborated on Paul Schrader’s screenplay.

In moments like these and many others, the profound intimacy and rich detail offered by Scorsese and deftly drawn out by Miller add a fresh dimension to a life story that could easily be an epic film in itself. While the broad strokes of Scorsese’s biography and illustrious career are widely known – from his Catholic upbringing as an asthmatic, movie-obsessed boy in New York’s Little Italy to his diverse filmography including Mean Streets (1973) and Killers of the Flower Moon (2023) – this five-part series unfolds like one continuous, deeply reflective, and often witty conversation.

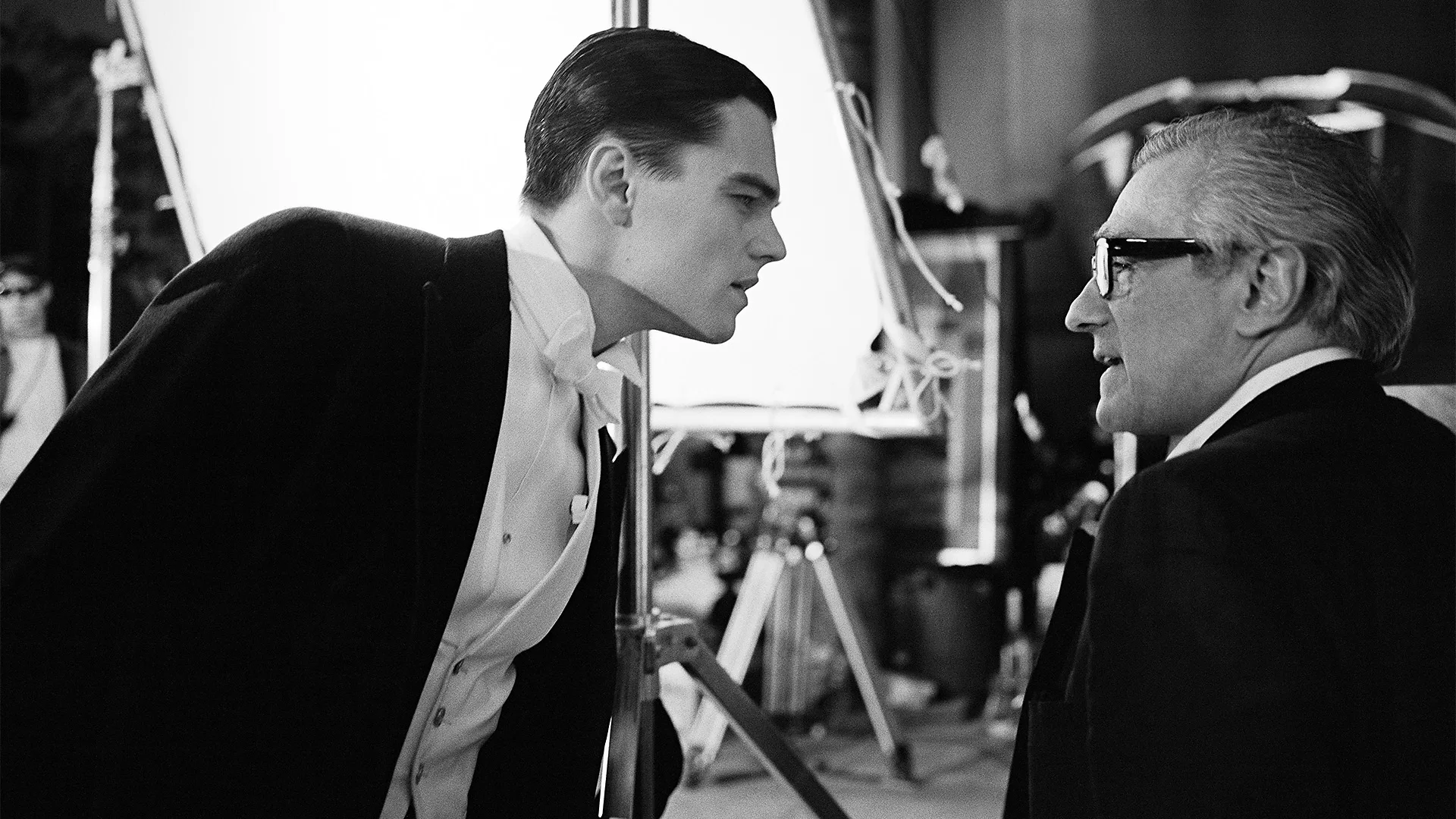

Scorsese, now 82, speaks matter-of-factly about his professional and personal shortcomings, often with a self-deprecating laugh. Rebecca Miller (whose notable films include Personal Velocity and Maggie’s Plan) remains off-camera, yet her voice is heard posing incisive questions. She gained unparalleled access to Scorsese’s personal archives and closest confidantes. The documentary masterfully weaves together glimpses of his iconic films with candid family photographs and insightful comments from long-time collaborators such as Robert De Niro, Leonardo DiCaprio, his esteemed editor Thelma Schoonmaker, and screenwriter Paul Schrader. This meticulous approach creates a compelling narrative, revealing the man behind the camera.

The Moral Compass: Religion and Cinema

Isabella Rossellini, one of Scorsese’s five wives, offers a succinct but profound observation to Miller: “I would say Marty is a saint/sinner.” She elaborates that he is saintly in his relentless pursuit of profound questions about good and evil, yet often admits to acting badly. Her insight hits home. What emerges most powerfully from the series, skillfully underscored by its editing, is the portrait of an artist perpetually grappling with moral choices. His brief, youthful consideration of becoming a priest left an indelible mark, as a constant interrogation of one’s moral compass permeates his life and deeply infuses his cinematic works.

Scorsese reflects on his drug-fueled years, using religious terminology to describe the allure: “The problem is, you enjoy the sin.” Later, he asserts that the gift of filmmaking is “a religious connection,” a “sacred thing,” revealing how profoundly his worldview is shaped by his spiritual perspective. This vision, in turn, molds his artistry. He was instrumental in transforming 20th-century cinema with bold, intellectually stimulating films such such as Taxi Driver (1976) and Goodfellas (1990). These works uniquely blend a kinetic, virtuosic directorial style with a raw, visceral understanding of the dark yet compelling undercurrents of human misbehavior.

Formative Years and Enduring Influences

The earliest episodes of the series meticulously establish the enduring influence of Scorsese’s formative years. Miller interviews childhood friends, some of whom were more inclined toward trouble than others. Notably, the brother of one friend—Salvatore Uricola, affectionately known as Sally Gaga back then—served as a key inspiration for Robert De Niro’s volatile character, Johnny Boy, in Mean Streets, a film deeply rooted in Scorsese’s old neighborhood. “Did you blow up a mailbox?” Miller inquires. “Yeah,” Sally Gaga replies, a confession juxtaposed on a split screen with a grinning Johnny Boy fleeing an exploding mailbox in the movie.

The series offers a reminder that his career has had more ups and downs than most people might think

Scorsese’s father, while keeping a clean record himself, often had to intervene to protect his brother, the filmmaker’s uncle Joe “The Bug” Scorsese, who provided another crucial inspiration for Johnny Boy. Even for those well-versed in Scorsese’s story, the detail about Joe the Bug is a fresh revelation. Throughout the documentary, Scorsese reveals surprising ways his boyhood continues to inform his art. His chronic asthma kept him indoors, observing the street from an upper-floor window. “That’s why I like high-angle shots,” he explains, connecting a childhood limitation to a signature cinematic style.

The documentary also serves as a poignant reminder that, despite his current acclaim as one of the greatest living filmmakers, Scorsese’s career has seen more peaks and valleys than many might imagine. Robert De Niro again convinced a reluctant Scorsese to make The King of Comedy (1982), a film Scorsese sometimes didn’t even want to be on set for until the afternoon. “I didn’t want to be there,” he confesses. Although now celebrated as a brilliant, prescient exploration of fame and fan obsession, the film was initially a box-office flop.

Scorsese eventually recovered from this commercial downturn, but more than a decade later, the box-office failures of Kundun (1997) and Bringing Out the Dead (1999) left his career, in his own words, “dead again.” It was Leonardo DiCaprio’s considerable influence that helped secure funding for Gangs of New York (2002), effectively reversing this latest professional setback and ushering in another successful phase of his career.

It’s also easy to overlook how controversial some of his films were upon release, primarily due to their intense violence, most notably Taxi Driver and its unsettling anti-hero, Travis Bickle. Scorsese reveals that upon reading Paul Schrader’s screenplay, it felt “almost as if I had written it myself.” When Miller asks what part of himself he felt most present in that film, he pauses, carefully choosing his words to clarify that he neither acts like nor condones Travis Bickle, before answering: “The anger, the loneliness, no way of really connecting with people” – a profound sense of being an outsider he links back to his working-class roots, which made him feel out of place at New York University film school and in Hollywood. “Violence is scary in yourself. Are you capable of it?” he reflects, adding that on-screen violence can be positive “if it’s truthful violence.”

Taxi Driver controversially re-entered headlines in 1981 when John Hinckley, obsessed with Jodie Foster’s child prostitute character in the film, shot Ronald Reagan. Isabella Rossellini recalls Scorsese wearing a bullet-proof vest to the Academy Awards that year, which were postponed by a day after the shooting.

Beyond the Camera: Glimpses of Private Life

The documentary does not extensively delve into Scorsese’s private life. He acknowledges that his demanding work made him a distant father to his two older children from different marriages, though all three of his children are interviewed and maintain good relationships with him today. He made a conscious effort to be present for Francesca, his youngest child, who recently helped transform him into a TikTok star with popular videos like “Dad Guesses Slang.”

When Scorsese becomes circumspect, Miller skillfully provides additional context. He mentions experiencing panic attacks while making Gangs of New York, vaguely attributing them to “people are sick.” Miller then subtly inserts a photograph of his wife, Helen, to whom he has been married for 26 years. Francesca later reveals that her mother was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease even before that period. A brief, heartfelt glimpse of the three of them at home offers as personal a look into his current life as the documentary provides.

A Rich and Bracing Portrait of a Master

While a five-hour documentary can only cover so much, some nuanced aspects could have been explored further. For instance, what Schrader, in connection to Taxi Driver, terms a “Madonna/whore problem” has been a persistent, if evolving, dynamic throughout Scorsese’s career. While he doesn’t explicitly judge the sexually liberated women in his films, such as Margot Robbie’s character in The Wolf of Wall Street (2013), this dichotomy often surfaces, evident even in Lily Gladstone’s irreproachable heroine in Killers of the Flower Moon. The series might have benefited from a deeper exploration of this complex theme.

However, such minor omissions do little to detract from a series so rich with insights and so bracingly honest in its portrayal. It allows viewers to see Martin Scorsese today: still vital, deeply engaged in his craft, and continuously evolving as a master filmmaker. Mr. Scorsese is available on Apple TV+ from October 17.

★★★★★